Film review: Blue Ruin

But in Blue Ruin sophomore director Jeremy Saulnier breathes new life into the familiar on-screen memes - announcing himself as a major new talent on the indie film scene in the process.

The intriguing twist is to make the main protagonist - who we slowly learn is seeking vengeance for the brutal slaying of his parents - fairly normal. He’s not trained for years in martial arts, hasn’t stored up a cache of heavy artillery or obsessively recorded every facet of the crime that has so affected his life.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

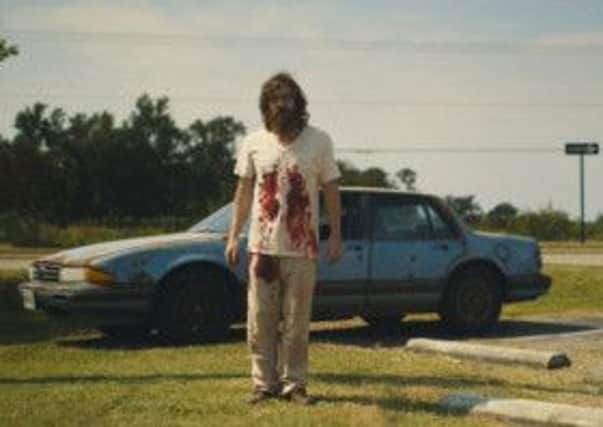

Hide AdInstead we have an initially mute, filthy and straggly-bearded Dwight (Macon Blair), who is living out of his car (the Blue Ruin of the title) courtesy of a chaotic and aimless lifestyle. He learns that the killer, Wade Cleland, is being released from jail and stages a clumsy - though effective - reprisal attack in a bar.

But the execution of Wade has consequences - with his hillbilly family swearing vengeance of their own and declaring war on Dwight and his surviving kin.

A swift shave, shower and change of clothes transforms Dwight outwardly, but there’s never any doubt that he’s still broken inside.

What follows is a film light on dialogue but heavy on atmosphere. An early scene involving Dwight being hunted by an assailant with a crossbow is a masterclass in combining the gruesomely violent with near-slapstick comedy; all the while maintaining the tension in a way which attracts positive comparisons with the Coen Brothers.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe plot constantly wrong-foots the audience, with regular revelations muddying the waters of the already-confused mission further.

The introduction of former school friend and ‘good ol’ boy’ Ben (a scene-stealing Devin Ratray) spices up the second act, though adds a somewhat clumsy comment on gun culture to proceedings.

Superfluous social commentary aside, Saulnier barely puts a foot wrong as he nudges his flawed assassin towards a final showdown via set pieces taking advantage of both rolling rural landscapes and claustrophobic homesteads.

Satisfyingly there’s no final triumphalism, just the certainty that violence is a blunt and inaccurate tool in any quest for redemption.