Incredible story of '˜The Black Scotsman' is now told on film

He spoke with a Scottish accent but his appearance shocked the young girl who served him in a local shop, so much so she was said to have exclaimed to her mother: “There’s a wee Scotty here that’s come back from Australia and he’s been burned black!”

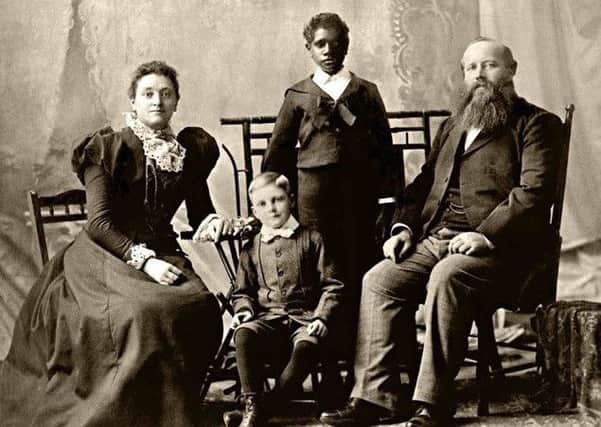

Thankfully Douglas wasn’t burnt black; he was an Aboriginal Australian who was visiting the hometown of his adopted parents Robert and Elizabeth Grant.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDouglas was born around 1885 into a rainforest indigenous nation in Queensland that had never seen a white person before.

Sadly, in 1887, this all changed when white miners, settlers and native police carried out a massacre.

The infant was found by taxidermists Robert and Elizabeth, who emigrated to Australia in the 1880s and were in the region on a collecting expedition for the Australian Museum.

Douglas, as he became known, was schooled in Sydney but loved Scottish culture. He could recite the poems of Robert Burns and speak in his parents’ accent.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe became a draughtsman and eventually fought in World War One.

Douglas first joined the Australian Army in early 1916, completing his training with the 34th Battalion, but was blocked from embarkation because Aboriginal Australians could not leave the country without permission.

He re-enlisted that August and was sent to France to join the 13th Battalion. However, the following April at the first ballet of Bullecourt he was wounded and captured.

In the German POW camps he was an object of curiosity as doctors, scientists and anthropologists sought to examine him, while sculptor Rudolf Markoeser modelled Douglas’s bust in ebony.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn December 1918 he was repatriated from Germany to England and took the opportunity to visit his adoptive wider family in Scotland.

The next year he sailed back to Sydney on a troop ship and, discharged from service, he returned to civilian life as a draughtsman at Mort’s Dock.

Not long after he left Mort’s Dock and moved to Lithgow, working as a labourer at a paper products factory and then at a small arms factory, he even had his own radio show.

Sadly, in 1931, not long after the death of his parents, Douglas suffered a breakdown – likely due to the effect of shell-shock – and returned to Sydney as clerk at a mental asylum where he also lived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn his later years, he lived at the Salvation Army’s old men’s quarters before his death in 1951 due to a subarachnoid haemorrhage and is buried at Botany Cemetery.

Something of a celebrity in his day, Douglas was forgotten for many years.

But Macquarie University historian Dr Tom Murray is trying to bring him back into the public consciousness.

Tom said: “The Australian frontier in the 1800s was a wild-west, and Frontiersmen basically ‘cleared’ the country of Aboriginal people in order to farm etc.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“For many Scots coming to Australia as a result of Highland Clearances and the like it was another mass war for land and control.

“The Grants happened to be in the same area as a massacre of Aboriginal people and ended up saving a young boy from what many thought was certain death.

“He was pretty famous in Australia in the 1920s but then got forgotten – as often happens. He wrote for newspapers and was seen as a ‘human experiment’ which proved that Aboriginal people could be civilised.

“His story became significant again when people began to personalise the bravery and sacrifice of veterans as part of the World War One centenary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I made a radio documentary about his life story for ABC, with the story of Douglas going to Scotland recounted by one of his war mates in the 1950s.

“My short film The Skin of Others is set in 1921 as Douglas meets Australia’s most famous poet of the 19th century Henry Lawson.

“They have a night of war stories and beer and sing Burns songs and The Bonnie Banks o’ Loch Lomond.

“Sometimes called The Black Scotsman, Douglas was extremely proud of his Scottish heritage and was renowned in Sydney for his poems and songs.

“I hope people in Motherwell will enjoy learning about his life.”